Looking for:

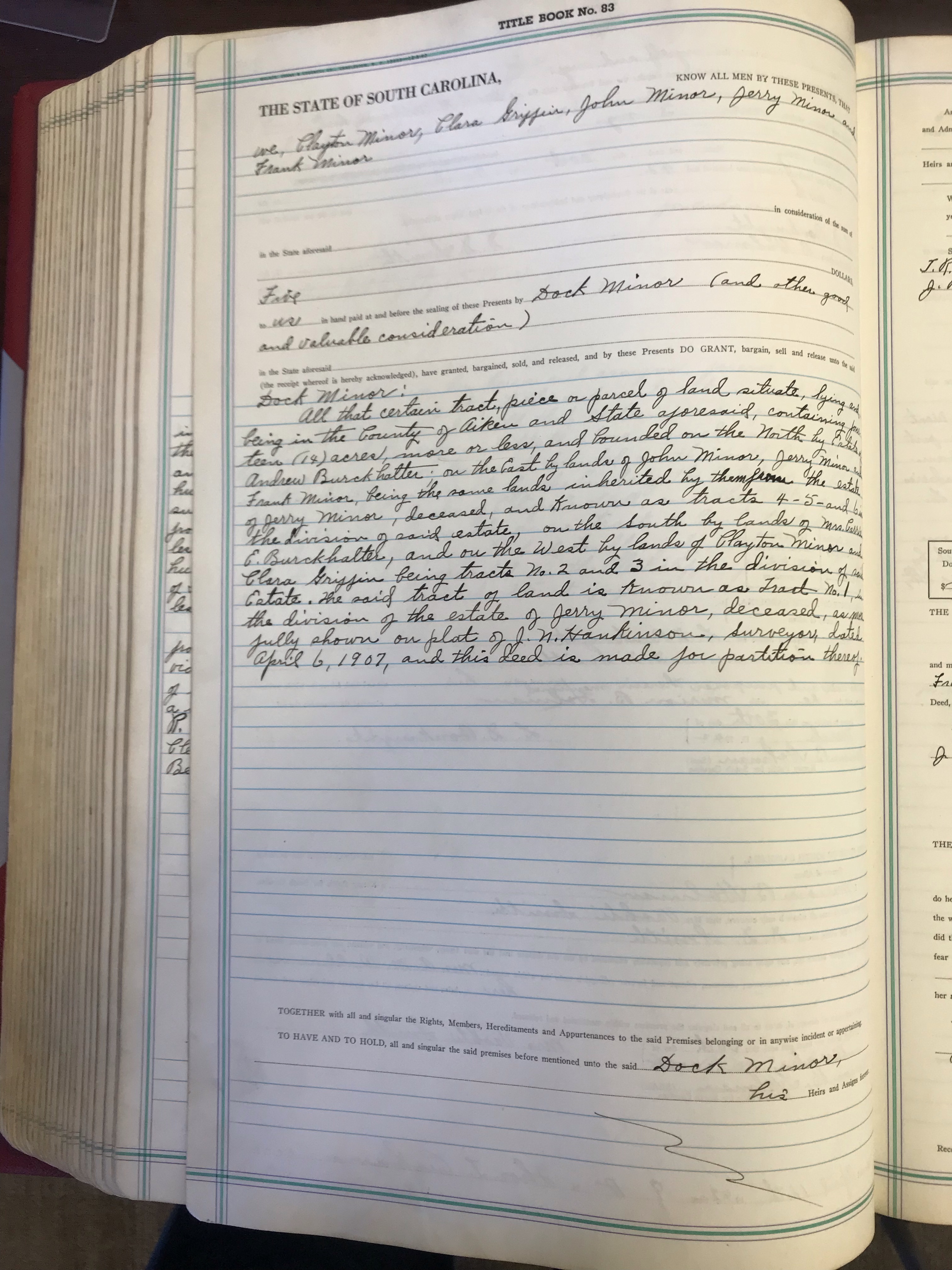

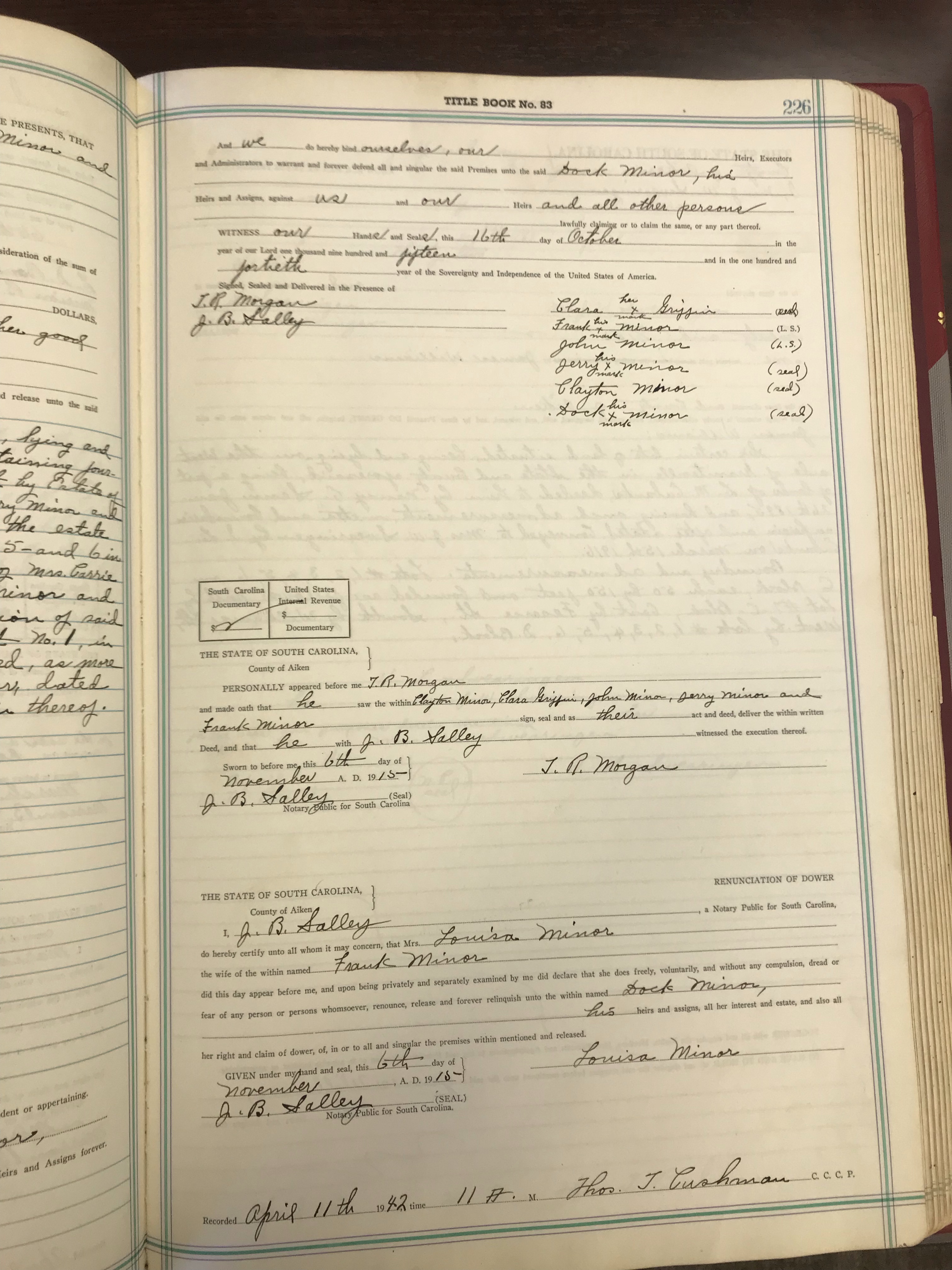

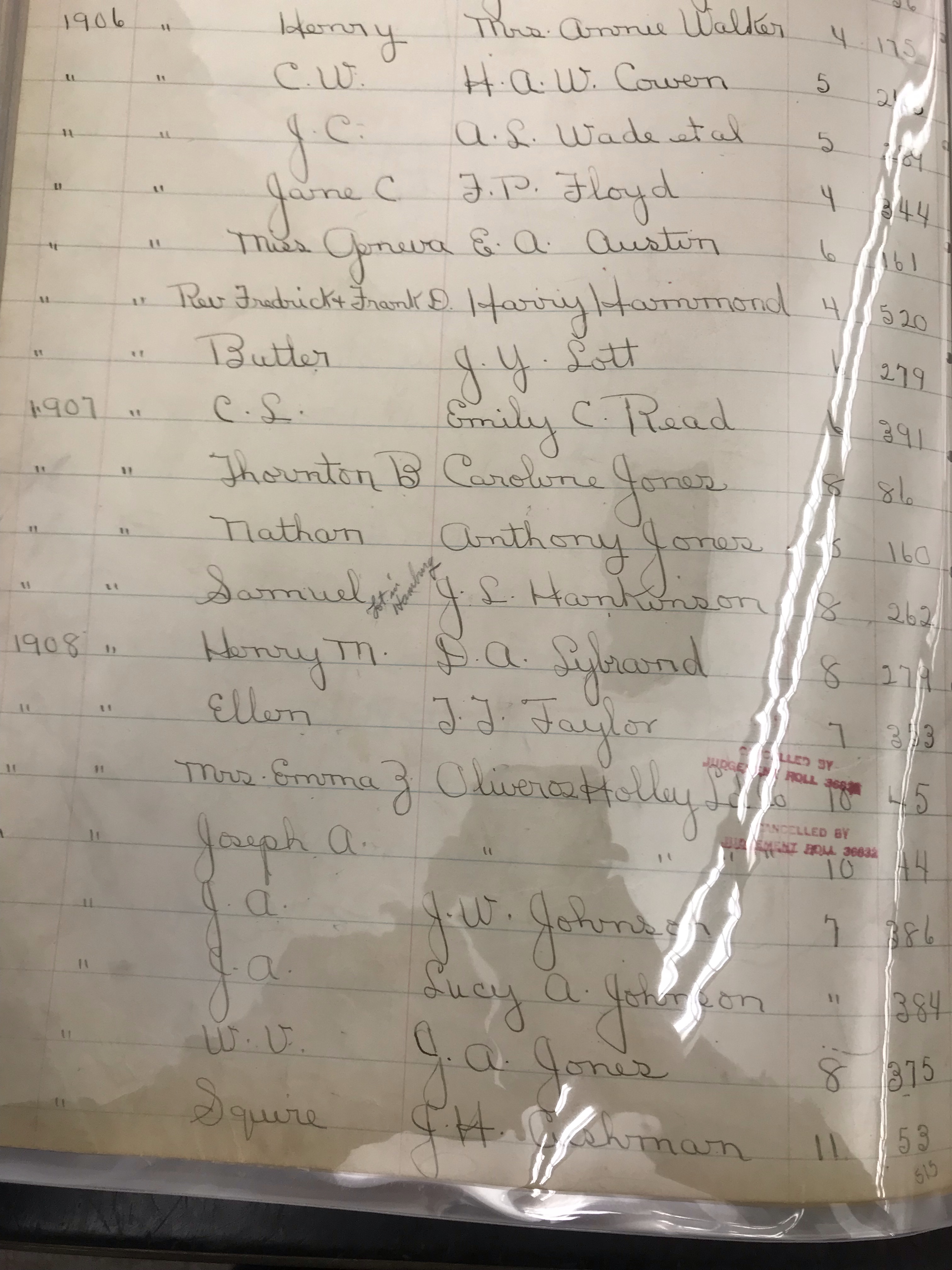

Who owned the land before Shultz?

1600 Thomas Minor

1654

The arrival of the first enslaved people in Suffolk County in 1654 marks only the beginning of a long, often intentionally ignored, chapter in Long Island history.

Long Island was home to the largest population of enslaved people in the northern colonies. Nathaniel Sylvester brought Suffolk County’s first enslaved people to Sylvester Manor on Shelter Island in 1654, starting the first of the few plantations on Long Island.

Now the manor is an educational farm where house tours are given. There are more than 10,000 documents that record life on the manor, but few focus on enslaved people. This is not uncommon.

“It has sort of been that history that was forgotten to be remembered, or they remembered to forget it,” Donnamarie Barnes, curator and archivist at Sylvester Manor, said. Read More

1712

1700’s

ANTONIA GIBSON

Colony of South Carolina Established

1720

Printed in Anderson’s Constitutions of 1738, it is states, “Earl Loudon granted a deputation to John Hammerton, Esq., to be Provincial Grand Master of South Carolina, in America.”

The CONSTITUTIONS OF THE FREE-MASONS

1723

1732

Mason- Dixon Line Established

1735

Lord Weymouth Thomas Thynne, 2nd Viscount

Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of England Grants John Hammerton as

Provincial Grand Master of South Carolina

John Hammerton

October 28, 1736

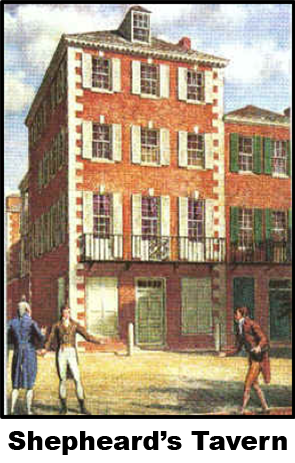

Solomon’s Lodge number one of Charleston

First met at Shepheard’s Tavern on the corner of Church and Broad Streets.

Solomon Lodge #1, South Carolina’s first Lodge, received its warrant from Thomas Thynne, 2nd Viscount Weymouth, the Grand Master of the Grand Lodge in England, in 1735.

It was listed as number 45 in “List of Lodges as altered by the Grand Lodge, April 18, 1792”.

Saturday, August 4, 1753

George Washington Raised at Fredericksburg Lodge No.4

William Burrows (1725-1781)

born and educated in London. Shortly after graduating in 1743 he moved to South Carolina and practiced law in Berkley county. He served as Worshipful Master of Solomon #1 in 1754. He built a wonderful home in Charleston at 71 Broad St. which is no longer standing. The house later served as one of Charleston’s leading hotels during the 1800’s.

He was one of the “Seventeen Gentlemen” who along with John Lining, founded the Charleston Library Society.

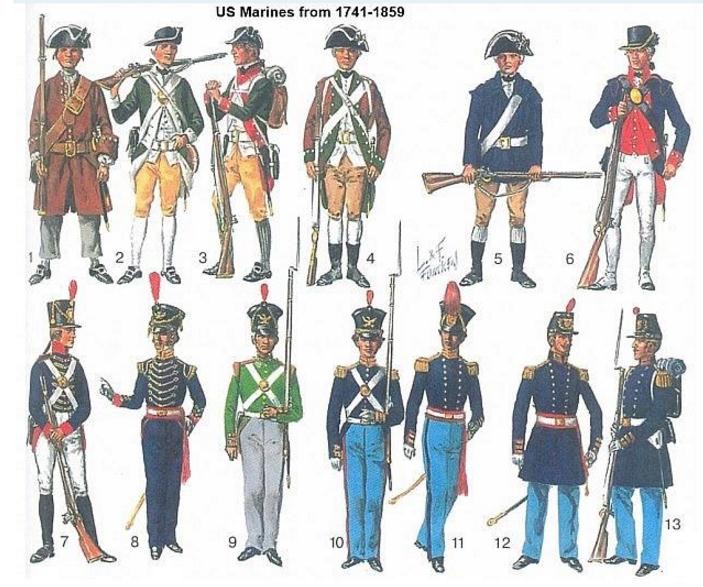

His son, William Ward Burrows, served in the Revolutionary War in South Carolina. Later he helped create the United States Marine Corp. and was appointed the Corp’s first Major Commandant by President John Adams.

1772

START

1779

Mason-Dixon Line Extended Westward

1780

Temporal Masonry Introduced in South Carolina

Commandery, No. 1, of Knights Templar at Charlestown

is now the representative of the body in which such degrees were first given; with only occasional interruption, such Commandery has continued to work from that period to the present time. It is probably the oldest Commandery in the United States.

December 1782

The Accepted and Ancient Scottish Rite Established

by a Sublime Grand Lodge of Perfection, at Charleston

1787

1788

June 21, 1788

The Constitution of the United States

“As It Is”

the supreme law of the

United States of America.

It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation’s first constitution, in 1789.

Second Grand Lodge of South Carolina

The Grand Lodge of Ancient York Masons

The original Grand Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons, also known as the “Moderns”

1797

John Adams, President

First meeting of the Supreme Council of the Scottish Rite

at Sheppard’s Tavern in South Carolina

1807

The importation of enslaved Africans was made illegal in the United States in 1807.

1808

Rev. Frederick Dalcho

Dr. Dalcho was elected, Corresponding Grand Secretary of the Grand Lodge of Ancient York Masons, and from that time directed the influences of his high position to the reconciliation of the Masonic difficulties in South Carolina.

1814

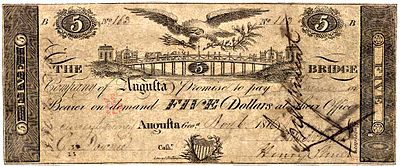

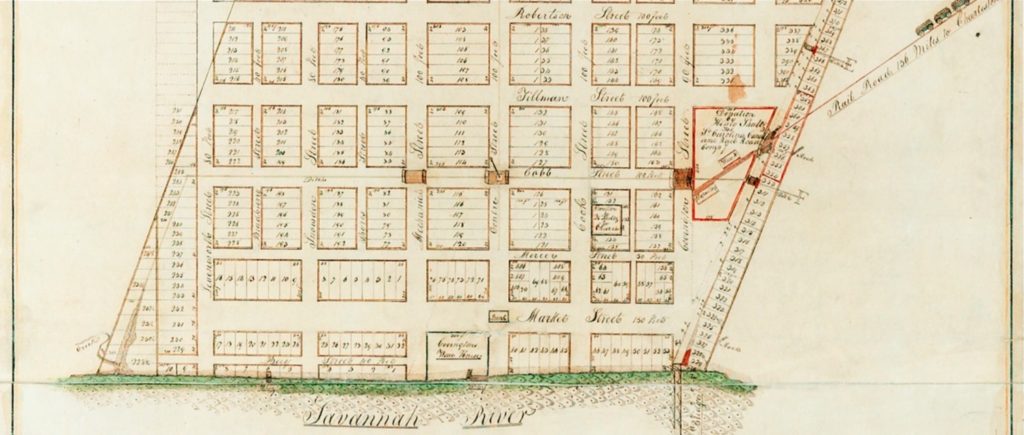

Building of the Savannah River bridge at Augusta

Henry Shultz engaged the support of a ‘mechanic’ named Lewis Cooper, secured financing, and drove the construction of a Savannah River bridge at Augusta. Two previous bridges had been swept away by floods, but his bridge proved remarkably durable and served the city well until 1888

1817

Solomon’s Lodge number 1 Merges with the Grand Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons

To form:

Is the beginning of the Civil War?

The Grand Lodge of Ancient Freemasons of South Carolina

Supreme Council of the thirty-third degree (established in Charleston in 1801) is considered the mother council of the world by Scottish Rite Freemasons.

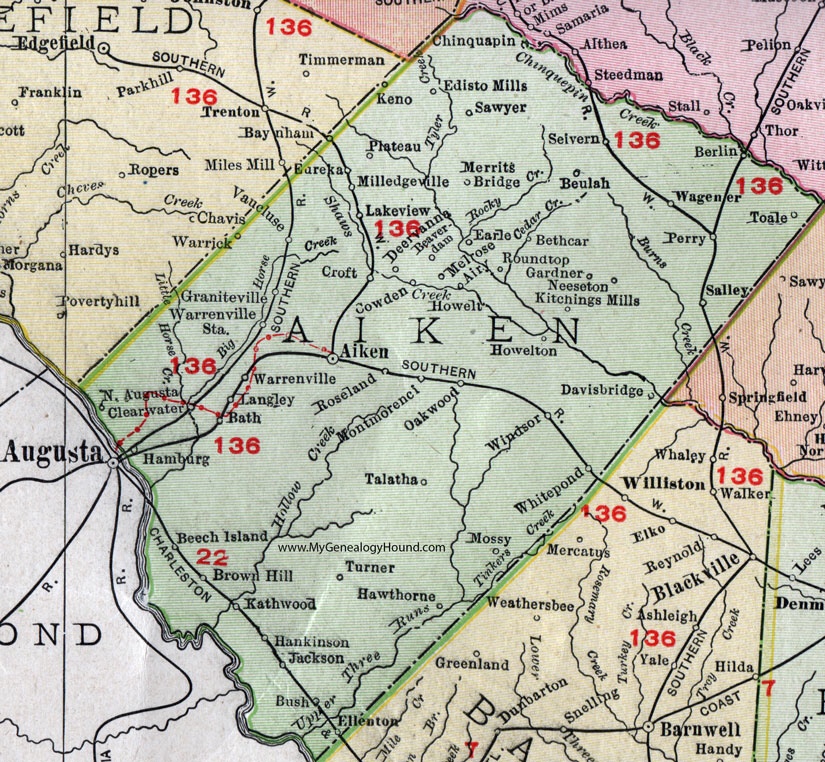

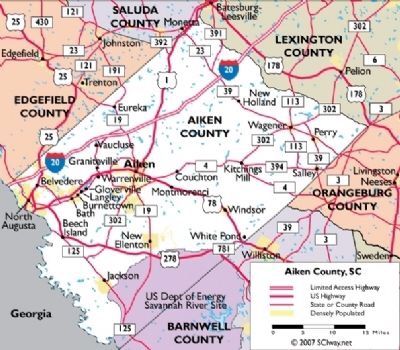

1821

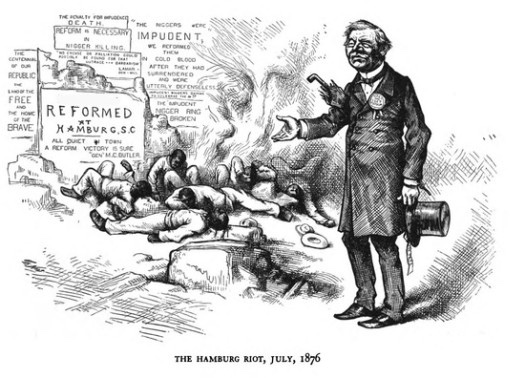

Shultz enlisted the support of property owners on the opposite side of the river, and in 1821 founded the town of Hamburg, South Carolina. The town grew quickly and by the end of 1821 had 84 houses and 200 inhabitants, directly competing with Augusta in its role as an upriver trading point. Shultz ruled the town as its ‘proprietor’ and worked continuously to improve it by constructing buildings, streamlining its water and road connections, and encouraging the opening of a bank.

“Bridge Bill”

February, 1822

Frederick Dalcho Resigns as Grand Commander.

Dr. Auld issued a new

Letters of Constitution for the Council of Princes of Jerusalem

at Charleston, inactive since the fire of 1819. It was issued to Illustrious Brothers Moses Holbrook, Horatio Gates Street, Alexander McDonald, Robert Carr, and Joseph McCosh. Dr. Auld signed this document as Acting Grand Commander, and it was signed also by Dr. James Moultrie as Acting Lieutenant Grand Commander, and by Moses Clava Levy as the Treasurer General.

1825

The membership of the Supreme Council stood as follows at the close of the year:

ISSAC AULD, Grand Commander, Moses Holbrook, Lieutenant Grand Commander, James Moultrie, Secretary General, M. C. Levy, Treasurer General, Horatio G. Street, Alexander McDonald, Joseph McCosh, John Barker, Joseph Eveleth (Massachusetts), John Roche, Giles F. Yates, (New York), Frederick Dalcho, Past Grand Commander

November 24, 1836

Rev. Frederick Dalcho Dies.

(Oration before the Medical Society by Dr. Frederick Dalcho on December 24th, 1805).

Henry Shultz establishes Hamburg.

1835

Bank of Hamburg established

1839

August 24, 1839

In need of navigation, the Africans ordered Montes and Ruiz to turn the ship eastward, back to Africa. But the Spaniards secretly changed course at night, and instead the Amistad sailed through the Caribbean and up the eastern coast of the United States. On August 26, the U.S. brig Washington found the ship while it was anchored off the tip of Long Island to get provisions. The naval officers seized the Amistad and put the Africans back in chains, escorting them to Connecticut, where they would claim salvage rights to the ship and its human cargo.

SOURCE

Slave Ship, Amastad Anchored, Long Island, New York

1840-1850

“Floods of Hamburg,”

White People abandon Hamburg.

1841

March 9, 1841

The United States vs. The Amistad Verdict:

40 U.S. 518; 10 L. Ed. 826

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

JANUARY, 1841 Term

1843

Albert Mackey (1807-1881)

Albert Mackey was born in Charleston in 1807. He was a physician, journalist and educator. He attended College of South Carolina (later to become gaged in philanthropic activities. He was a charter member of the board of trustees of South Carolina College (later the University of South Carolina) in 1832, graduated from the medical department and was appointed in 1838 as demonstrator of anatomy.

In 1844, he devoted himself to writing on a variety of subjects including languages, the Middle Ages, and Freemasonry. This led to his investigation of abstruse symbolism, Cabalistic, and Talmudic research.

With regard to his writing on Freemasonry his contributions were prodigious and include: A Lexicon of Freemasonry; Tame True Mystic Tie; The Ahiman Rezon of South Carolina; Principles of Masonic Law; Text-Book of Masonic Jurisprudence; History of Freemasonry in South Carolina; Manual of the Lodge; Cryptic Masonry Symbolism of Freemasonry, and Masonic Ritual; Encyclopedia of Freemasonry; and Masonic Parliamentary Law

Albert Mackey was raised to Master Mason in St. Andrews Lodge in 1841. Shortly thereafter he affiliated with Solomon Lodge where he served as Worshipful Master in 1843. He served as Grand Lecture and Grand Secretary of the Grand Lodge of South Carolina. He also served as Secretary General of the Supreme Council of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite for the Southern Jurisdiction of the United States.

He ran for United States Senate in South Carolina in 1868 but was defeated.

He moved to Washington, D.C. in 1870 and died in Virginia the following year.

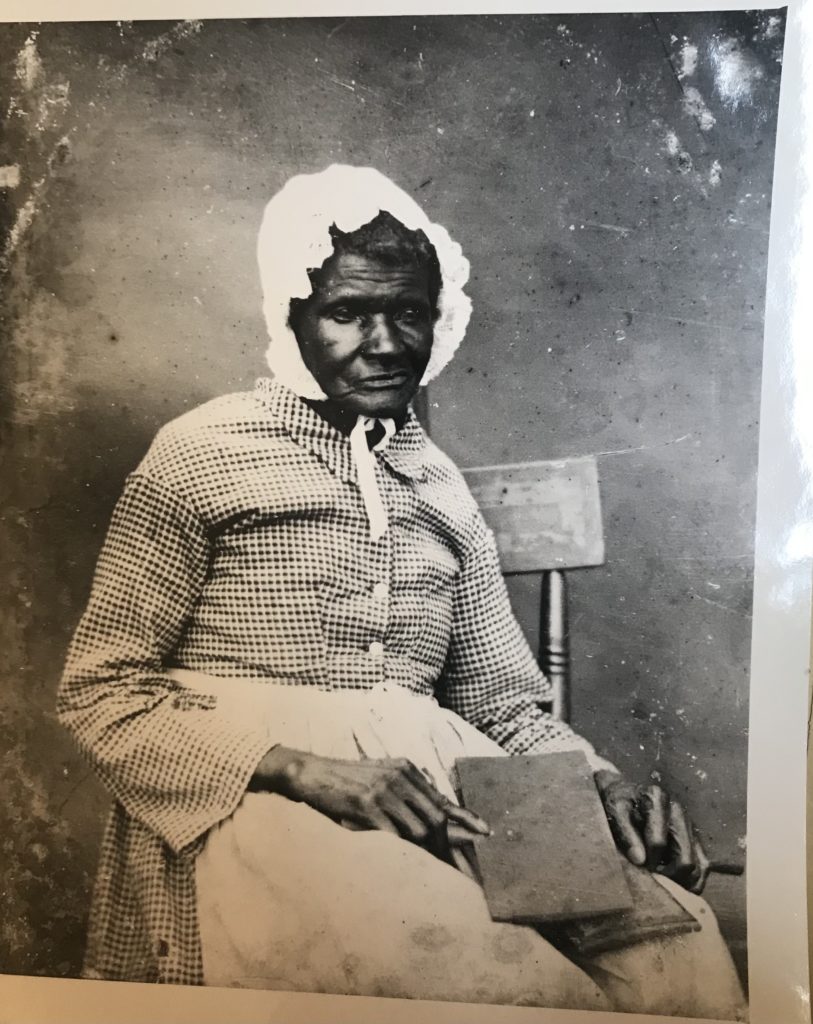

1850

1851

October 13, 1851 Henry Shultz Dies in Hamburg

Freed (Black) Men settle in Hamburg.

1853

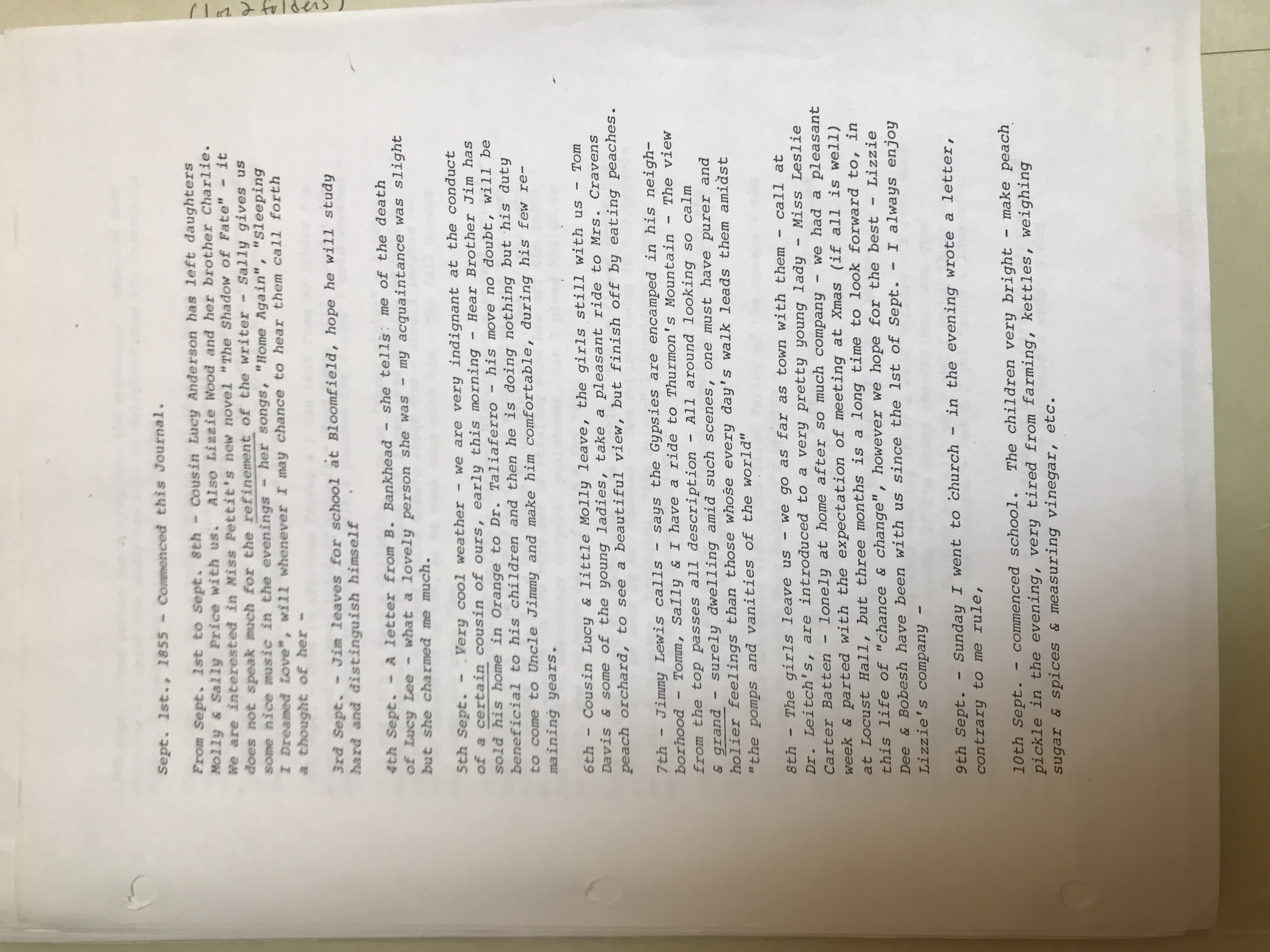

September 1, 1855:

Louisa Virginia Minor Diary

Louisa Virginia Minor Death

1862

September 22, 1862

The Emancipation Proclamation

“

January 1, 1863

By the President of the United States of America:

A Proclamation.

Whereas, on the twenty-second day of September, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-two, a proclamation was issued by the President of the United States, containing, among other things, the following, to wit:

“That on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the Executive Government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.

“That the Executive will, on the first day of January aforesaid, by proclamation, designate the States and parts of States, if any, in which the people thereof, respectively, shall then be in rebellion against the United States; and the fact that any State, or the people thereof, shall on that day be, in good faith, represented in the Congress of the United States by members chosen thereto at elections wherein a majority of the qualified voters of such State shall have participated, shall, in the absence of strong countervailing testimony, be deemed conclusive evidence that such State, and the people thereof, are not then in rebellion against the United States.”

Now, therefore I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, by virtue of the power in me vested as Commander-in-Chief, of the Army and Navy of the United States in time of actual armed rebellion against the authority and government of the United States, and as a fit and necessary war measure for suppressing said rebellion, do, on this first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, and in accordance with my purpose so to do publicly proclaimed for the full period of one hundred days, from the day first above mentioned, order and designate as the States and parts of States wherein the people thereof respectively, are this day in rebellion against the United States, the following, to wit:

Arkansas, Texas, Louisiana, (except the Parishes of St. Bernard, Plaquemines, Jefferson, St. John, St. Charles, St. James Ascension, Assumption, Terrebonne, Lafourche, St. Mary, St. Martin, and Orleans, including the City of New Orleans) Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia, (except the forty-eight counties designated as West Virginia, and also the counties of Berkley, Accomac, Northampton, Elizabeth City, York, Princess Ann, and Norfolk, including the cities of Norfolk and Portsmouth[)], and which excepted parts, are for the present, left precisely as if this proclamation were not issued.

And by virtue of the power, and for the purpose aforesaid, I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free; and that the Executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons.

And I hereby enjoin upon the people so declared to be free to abstain from all violence, unless in necessary self-defence; and I recommend to them that, in all cases when allowed, they labor faithfully for reasonable wages.

And I further declare and make known, that such persons of suitable condition, will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.

And upon this act, sincerely believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind, and the gracious favor of Almighty God.

In witness whereof, I have hereunto set my hand and caused the seal of the United States to be affixed.

Done at the City of Washington, this first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty three, and of the Independence of the United States of America the eighty-seventh.

By the President: ABRAHAM LINCOLN

WILLIAM H. SEWARD, Secretary of State.”

The Homestead Act

“

CHAP. LXXV. —An Act to secure Homesteads to actual Settlers on the Public Domain.

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That any person who is the head of a family, or who has arrived at the age of twenty-one years, and is a citizen of the United States, or who shall have filed his declaration of intention to become such, as required by the naturalization laws of the United States, and who has never borne arms against the United States Government or given aid and comfort to its enemies, shall, from and after the first January, eighteen hundred and sixty-three, be entitled to enter one quarter section or a less quantity of unappropriated public lands, upon which said person may have filed a preemption claim, or which may, at the time the application is made, be subject to preemption at one dollar and twenty-five cents, or less, per acre; or eighty acres or less of such unappropriated lands, at two dollars and fifty cents per acre, to be located in a body, in conformity to the legal subdivisions of the public lands, and after the same shall have been surveyed: Provided, That any person owning and residing on land may, under the provisions of this act, enter other land lying contiguous to his or her said land, which shall not, with the land so already owned and occupied, exceed in the aggregate one hundred and sixty acres.

SEC. 2. And be it further enacted, That the person applying for the benefit of this act shall, upon application to the register of the land office in which he or she is about to make such entry, make affidavit before the said register or receiver that he or she is the head of a family, or is twenty-one years or more of age, or shall have performed service in the army or navy of the United States, and that he has never borne arms against the Government of the United States or given aid and comfort to its enemies, and that such application is made for his or her exclusive use and benefit, and that said entry is made for the purpose of actual settlement and cultivation, and not either directly or indirectly for the use or benefit of any other person or persons whomsoever; and upon filing the said affidavit with the register or receiver, and on payment of ten dollars, he or she shall thereupon be permitted to enter the quantity of land specified: Provided, however, That no certificate shall be given or patent issued therefor until the expiration of five years from the date of such entry; and if, at the expiration of such time, or at any time within two years thereafter, the person making such entry; or, if he be dead, his widow; or in case of her death, his heirs or devisee; or in case of a widow making such entry, her heirs or devisee, in case of her death; shall. prove by two credible witnesses that he, she, or they have resided upon or cultivated the same for the term of five years immediately succeeding the time of filing the affidavit aforesaid, and shall make affidavit that no part of said land has been alienated, and that he has borne rue allegiance to the Government of the United States; then, in such case, he, she, or they, if at that time a citizen of the United States, shall be entitled to a patent, as in other cases provided for by law: And provided, further, That in case of the death of both father and mother, leaving an Infant child, or children, under twenty-one years of age, the right and fee shall ensure to the benefit of said infant child or children; and the executor, administrator, or guardian may, at any time within two years after the death of the surviving parent, and in accordance with the laws of the State in which such children for the time being have their domicile, sell said land for the benefit of said infants, but for no other purpose; and the purchaser shall acquire the absolute title by the purchase, and be entitled to a patent from the United States, on payment of the office fees and sum of money herein specified.

SEC. 3. And be it further enacted, That the register of the land office shall note all such applications on the tract books and plats of, his office, and keep a register of all such entries, and make return thereof to the General Land Office, together with the proof upon which they have been founded.

SEC. 4. And be it further enacted, That no lands acquired under the provisions of this act shall in any event become liable to the satisfaction of any debt or debts contracted prior to the issuing of the patent therefor.

SEC. 5. And be it further enacted, That if, at any time after the filing of the affidavit, as required in the second section of this act, and before the expiration of the five years aforesaid, it shall be proven, after due notice to the settler, to the satisfaction of the register of the land office, that the person having filed such affidavit shall have actually changed his or her residence, or abandoned the said land for more than six months at any time, then and in that event the land so entered shall revert to the government.

SEC. 6. And be it further enacted, That no individual shall be permitted to acquire title to more than one quarter section under the provisions of this act; and that the Commissioner of the General Land Office is hereby required to prepare and issue such rules and regulations, consistent with this act, as shall be necessary and proper to carry its provisions into effect; and that the registers and receivers of the several land offices shall be entitled to receive the same compensation for any lands entered under the provisions of this act that they are now entitled to receive when the same quantity of land is entered with money, one half to be paid by the person making the application at the time of so doing, and the other half on the issue of the certificate by the person to whom it may be issued; but this shall not be construed to enlarge the maximum of compensation now prescribed by law for any register or receiver: Provided, That nothing contained in this act shall be so construed as to impair or interfere in any manner whatever with existing preemption rights: And provided, further, That all persons who may have filed their applications for a preemption right prior to the passage of this act, shall be entitled to all privileges of this act: Provided, further, That no person who has served, or may hereafter serve, for a period of not less than fourteen days in the army or navy of the United States, either regular or volunteer, under the laws thereof, during the existence of an actual war, domestic or foreign, shall be deprived of the benefits of this act on account of not having attained the age of twenty-one years.

SEC. 7. And be it further enacted, That the fifth section of the act entitled “An act in addition to an act more effectually to provide for the punishment of certain crimes against the United States, and for other purposes,” approved the third of March, in the year eighteen hundred and fifty-seven, shall extend to all oaths, affirmations, and affidavits, required or authorized by this act.

SEC. 8. And be it further enacted, That nothing in this act shall be so construed as to prevent any person who has availed him or herself of the benefits of the first section of this act, from paying the minimum price, or the price to which the same may have graduated, for the quantity of land so entered at any time before the expiration of the five years, and obtaining a patent therefor from the government, as in other cases provided by law, on making proof of settlement and cultivation as provided by existing laws granting preemption rights.

APPROVED, May 20, 1862.”

Ninth Regiment National Guard of the State of South Carolina, All Black Militia, is Formed: (Company A)

Issued Arms by the State of South Carolina under:

Governor Robert Scott

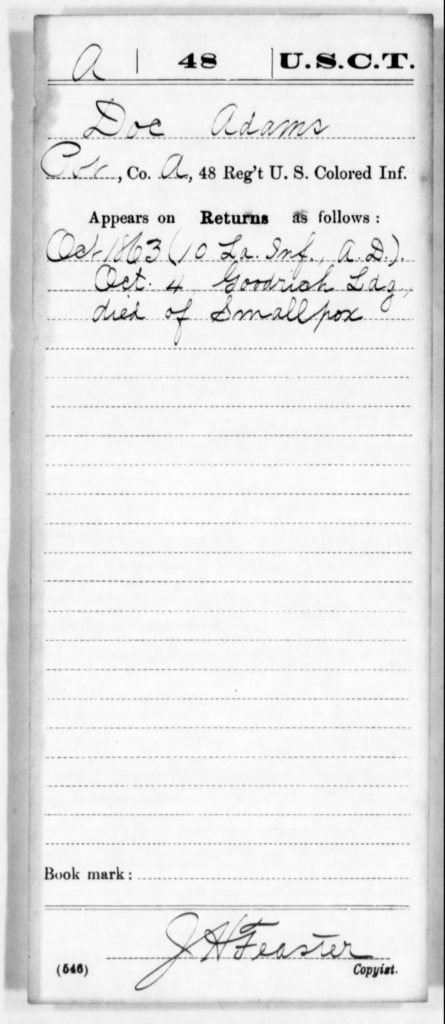

1863

1865

Jerry Minor

Member of:

Zion Branch Baptist Church

Brush Arbor

“The History of Brush Arbors

The Choctaw Indian Nation’s Burial Rituals

A brush arbor is a rough, open-sided shelter constructed of vertical poles driven into the ground with additional long poles laid across the top as support for a roof of brush, cut branches or hay. Appearing in the 1700’s and early 1800’s, brush arbors were used by some churches to protect worshipers from the weather during lengthy revival meetings.

Protracted Meetings

Brush arbor revivals began in the late 1700’s and were held regularly through the mid-1900’s. These “protracted meetings” could last for days or even weeks, with many people traveling for miles to attend and staying to camp on the grounds.

Circuit-riding Preachers

An itinerant minister or a preacher who rode circuit through rural communities would send word in advance of his expected arrival and the congregation would erect a brush arbor to house the revival meeting, usually at a crossroads in a well-traveled area.

When the Crowds Grew

Leafy branches overlaid the pole structure, blocking the hot summer sun and most rainfall. A pulpit was set up in the center front. When the crowds overwhelmed the space under the arbor, extensions could be built to accommodate them.

Brush Arbor Diary

An 1834 diary kept by Elizabeth Cummings gives details of a brush arbor meeting from the perspective of a young girl whose parents helped Brother Daniel Truelove, a Baptist circuit rider, erect a brush arbor for his revival.”

1940

Great, Great Uncle of Don Adams:

Terry Minor,

DR. KENNEDY

Park Avenue to Lawrence to Ridgeland to Newberry

Edgefield, South Carolina

Burckhalter

Last Slave Ship to arrive in port of:

Fill in the blank

Plantation

1001 Old Aiken Road

1845

Manifest Destiny and U.S. Westward Expansion

Yes, more, more, more! . . . . till our national destiny is fulfilled and . . . the whole boundless continent is ours – John L. O’Sullivan, 1845

The phrase “Manifest Destiny” originated in the nineteenth century, yet the concept behind the phrase originated in the seventeenth century with the first European immigrants in America, English Protestants or Puritans. Manifest Destiny is defined as “the concept of American exceptionalism, that is, the belief that America occupies a special place among the countries of the world.” The Puritans came to America in 1630 believing that their survival in the new world would be a sign of God’s approval. As their ship the Arbella neared shore, group leader John Winthrop gave a sermon entitled “A Modell [sic] of Christian Charity,” in order to prepare his fellow passengers for what lay ahead. His sermon stressed the importance of this experimental religious settlement in the new world, and how it would come to serve as an example for all settlements thereafter, stating “For wee [sic] must consider that wee [sic] shall be as a citty [sic] upon a hill. The eies [sic] of all people are upon us.” Winthrop also recalled God’s instruction in the Bible about the need to expand and prosper, “Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it.” The ideology of Manifest Destiny continued through the eighteenth-century as victorious America won independence from Great Britain, an event that many occasioned to be preordained and lauded by God and an example of American exceptionalism.

The use of the term “Manifest Destiny” did not enter conventional conversation until 1845, when journalist John Louis O’Sullivan wrote that it was “our manifest destiny to overspread and to possess the whole of the continent which Providence has given us for the development of the great experiment of liberty and federated self-government entrusted to us.” Nineteenth-century expansionism went hand in hand with the concept of Manifest Destiny, each signaling that there was a God-given, sanctioned right to conquer the land and displace the “uncivilized,” non-Christian peoples who, it was believed, did not take full advantage of the land which had been given to them. This ideology served as justification for the violent displacement of native peoples and the forceful takeovers of land by military means. Nineteenth-century Americans expanded upon Winthrop’s notion of “a city upon a hill” to encompass the idea that all countries should look to the United States as a model nation. Just as sixteenth-century Puritans had seen it as their divine right to “tame and cultivate” the frontier, so too did nineteenth-century capitalists and politicians see the expansion of the frontier as providential, their personal and professional profit in harmony with the nation’s economic development.

U.S. Territorial Expansion

American Progress, 1872, John Gast, Library of Congress

The European settlers who came to America in search of a new life believed that land acquisition was crucial to their future prosperity. Following the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 from France and the subsequent exploration of that western territory by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, the nation’s appetite for expansion grew. The Louisiana Purchase, which tripled the size of the young country, effectively started a chain reaction for U.S. territorial expansion. The next fifty years of American history saw the nation increase its land holdings exponentially: in 1845 Texas was incorporated into the U.S.; Britain’s 1846 treaty with the U.S. gained the young nation the disputed Oregon territory; California, Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada and Utah were incorporated following the 1848 war with Mexico; and finally, in 1853, the Gadsden Purchase completed the last contiguous land purchase in the continental U.S., finalizing the southern borders of New Mexico and Arizona as we know them today. In 1846 Walt Whitman wryly opined on the relentless territorial expansion, stating “The more we reflect upon annexation as involving a part of Mexico, the more do doubts and obstacles resolve themselves away. . . . Then there is California, on the way to which lovely tract lies Santa Fe; how long a time will elapse before they shine as two new stars in our mighty firmament?”

Manifest Destiny, in U.S. history, the supposed inevitability of the continued territorial expansion of the boundaries of the United States westward to the Pacific and beyond. Before the American Civil War (1861–65), the idea of Manifest Destiny was used to validate continental acquisitions in the Oregon Country, Texas, New Mexico, and California. The purchase of Alaska after the Civil War briefly revived the concept of Manifest Destiny, but it most evidently became a renewed force in U.S. foreign policy in the 1890s, when the country went to war with Spain, annexed Hawaii, and laid plans for an isthmian canal across Central America.

Origin of the term

John L. O’Sullivan, the editor of a magazine that served as an organ for the Democratic Party and of a partisan newspaper, first wrote of “manifest destiny” in 1845, but at the time he did not think the words profound. Rather than being “coined,” the phrase was buried halfway through the third paragraph of a long essay in the July–August issue of The United States Magazine, and Democratic Review on the necessity of annexing Texas and the inevitability of American expansion. O’Sullivan was protesting European meddling in American affairs, especially by France and England, which he said were acting

for the avowed object of thwarting our policy and hampering our power, limiting our greatness and checking the fulfillment of our manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions.

O’Sullivan’s observation was a complaint rather than a call for aggression, and he referred to demography rather than pugnacity as the solution to the perceived problem of European interference. Yet when he expanded his idea on December 27, 1845, in a newspaper column in the New York Morning News, the wider audience seized upon his reference to divine superintendence. Discussing the dispute with Great Britain over the Oregon Country, O’Sullivan again cited the claim to

the right of our manifest destiny to overspread and to possess the whole of the continent which Providence has given us for the development of the great experiment of liberty and federated self-government entrusted to us.

Some found the opinion intriguing, but others were simply irritated. The Whig Party sought to discredit Manifest Destiny as belligerent as well as pompous, beginning with Massachusetts Rep. Robert Winthrop’s using the term to mock Pres. James K. Polk’s policy toward Oregon.

Get a Britannica Premium subscription and gain access to exclusive content.

Yet unabashed Democrats took up Manifest Destiny as a slogan. The phrase frequently appeared in debates relating to Oregon, sometimes as soaring rhetoric and other times as sarcastic derision. As an example of the latter, on February 6, 1846, the New-Hampshire Statesman and State Journal, a Whig newspaper, described “some windy orator in the House [of Representatives]” as “pouring for his ‘manifest destiny’ harangue.”

Over the years, O’Sullivan’s role in creating the phrase was forgotten, and he died in obscurity some 50 years after having first used the term “manifest destiny.” In an essay in The American Historical Review in 1927, historian Julius W. Pratt identified O’Sullivan as the phrase’s originator, a conclusion that became universally accepted.

A history of expansion

Despite disagreements about Manifest Destiny’s validity at the time, O’Sullivan had stumbled on a broadly held national sentiment. Although it became a rallying cry as well as a rationale for the foreign policy that reached its culmination in 1845–46, the attitude behind Manifest Destiny had long been a part of the American experience. The impatient English who colonized North America in the 1600s and 1700s immediately gazed westward and instantly considered ways to venture into the wilderness and tame it. The cause of that ceaseless wanderlust varied from region to region, but the behaviour became a tradition within one generation. The western horizon would always beckon, and Americans would always follow. After the American Revolution (1775–83), the steady advance of the cotton kingdom in the South matched the lure of the Ohio Country in the North. In 1803, Pres. Thomas Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase doubled the size of the country with the stroke of a pen. Expansionists eager to acquire Spanish Florida were part of the drive for the War of 1812, and many historians argue that American desires to annex Canada were also an important part of the equation. Andrew Jackson’s invasion of Florida in 1818 and the subsequent Transcontinental Treaty (Adams-Onís Treaty) settled a southern border question that had been vexing the region for a generation and established an American claim to the Pacific Northwest as Spain renounced its claim to the Oregon Country. The most consequential territorial expansion in the country’s history occurred during the 1820s. Spreading American settlements often caused additional unrest on the country’s western borders. As the United States pacified and stabilized volatile regions, the resulting appropriation of territory usually worsened relations with neighbours, setting off a cycle of instability that encouraged additional annexations.

Caught in the upheaval coincidental to that expansion, Southeast Indians succumbed to the pressure of spreading settlement by ceding their lands to the United States and then relocating west of the Mississippi River under Pres. Andrew Jackson’s removal policy of the 1830s. The considerable hardships suffered by the Indians in that episode were exemplified by the devastation of the Cherokees on the infamous Trail of Tears, which excited humanitarian protests from both the political class and the citizenry.

Finally, in the 1840s, diplomacy resolved the dispute over the Oregon Country with Britain, and victory in the Mexican-American War (1846–48) closed out a period of dramatically swift growth for the United States. Less than a century after breaking from the British Empire, the United States had gone far in creating its own empire by extending sovereignty across the continent to the Pacific, to the 49th parallel on the Canadian border, and to the Rio Grande in the south. Having transformed a group of sparsely settled colonies into a continental power of enormous potential, many Americans thought the achievement so stunning as to be obvious. It was for them proof that God had chosen the United States to grow and flourish.

Yet in a story as old as ancient Rome’s transformation from republic to empire, not all Americans, like the doubters of Rome, found it encouraging. Those dissenters saw rapid expansion as contrary to the principles of a true republic and predicted that the cost of empire would be high and its consequences perilous.

Listen to article6 minutes

The end of Manifest Destiny

Realizing its Manifest Destiny with triumph over Mexico in 1848 gave the United States an immense domain that came with spectacular abundance and potential. (Under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the war, the United States acquired more than 525,000 square miles [1,360,000 square km] of land, including present-day Arizona, California, western Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, and Utah.) California’s climate made much of it a natural garden, and its gold would finance decades of impressive growth. Burgeoning Pacific trade required opening diplomatic relations with heretofore isolationist Japan and created American trade in places that before had always been European commercial preserves. Yet the dispute over the status of the new western territories regarding slavery disrupted the American political system by reviving arguments that shattered fragile compromises and inflamed sectional discord.

In fact, those disputes brought the era of Manifest Destiny to an abrupt close. Plans to tie the eastern United States to the Pacific Coast with a transcontinental railroad led to the country’s final land acquisition before the Civil War when U.S. Minister to Mexico James Gadsden purchased a small parcel of land in 1853 to facilitate a southern route. For that reason alone, the Gadsden Purchase provoked the North, and Americans soon found themselves embroiled in additional arguments that foiled the railroad while killing any possible consensus for further expansion.

The New Manifest Destiny

After the Civil War, reconstructing the Union and promoting the industrial surge that made the United States a premier economic power preoccupied the country. In the 1890s, however, the United States and other great powers embraced geopolitical doctrines stemming from the writings of naval officer and historian Alfred Thayer Mahan, who posited that national greatness in a competitive world derived from the ability to control navigation of the seas. The coincidence of Mahanian doctrine emerging in tandem with Herbert Spencer’s belief that unfettered competition promoted progress led to a naval arms race that revolutionized seagoing architecture and hastened the replacement of sail with steam. Although they accommodated bigger guns and could meet schedules regardless of weather, fuel-hungry steamships required far-flung coaling stations, which encouraged naval powers to plant their flags on remote outposts and define their interest in places never before connected to their security or commerce.

Americans dubbed this freshly found national endeavour the “New Manifest Destiny.” As before, it was a way of clothing imperial ambitions in a higher purpose ostensibly decreed by Providence. The Spanish-American War of 1898 arose from popular outrage over Madrid’s reportedly barbarous colonial policies in Cuba and, more immediately, in response to the destruction of the U.S. battleship Maine, but it ended with the United States acquiring remnants of Spain’s dwindling global empire. Similarly, the annexation of Hawaii in 1898 provided the United States Navy with the desirable port facilities at Pearl Harbor.

The New Manifest Destiny curiously reversed the political lines of support of its forbearer. In the 1840s Manifest Destiny was primarily a Democrat Party doctrine over Whig dissent, but the New Manifest Destiny was a Republican program, especially under Pres. Theodore Roosevelt’s vigorous promotion of it, and Democrats tended to object to it. The Progressive wings of both parties, however, gravitated to advancing American idealism, which led to intervention in World War I and Pres. Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points as a statement of high globalism. Wilson’s program ultimately failed to sustain a consensus among the American people. Just as expansionism before the Civil War collapsed under the press of the slavery controversy, Wilsonian internationalism retreated before the United States’ traditional isolationism after the war.

Conflicting interpretations

Manifest Destiny has caused controversy among historians trying to sort out its origins and assess its significance. In 1893 historian Frederick Jackson Turner put forth what proved a durable interpretation in his seminal essay “The Significance of the Frontier in American History.” In Turner’s view, taming the western wilderness shaped the pioneers as much as they shaped the land they settled, making them robust and capable in continuing the American tradition of pacifying and inhabiting whatever lay beyond the western horizon. In that regard, Turner provided an explanation for American exceptionalism, but, beginning in the mid-1980s, scholars styling themselves New Western Historians challenged his ideas. They rejected the view that Americans were agents of change, let alone purveyors of progress. Rather, the New Western Historians stressed the role of the coalition of government and influential corporations in overwhelming indigenous populations. In addition, they did not see the West fundamentally shaping American exceptionalism, the existence of which they doubted in any case. They focused instead on how competing cultures melded to create a singular heritage that was nevertheless broad and varied.

Whatever the validity of those conflicting views, in the simplest interpretation Manifest Destiny expressed the American version of an age-old yearning for improvement, change, and growth. Those who promoted it might have done so from venal or virtuous motives, and those who opposed it were seemingly vindicated by the Civil War in their grim warnings about the steep costs of a spreading imperium, but the events of American expansionism were a tale more than twice-told in the course of history.David S. HeidlerJeanne T. Heidler

Table of Contents

- Introduction & Quick Facts

- Land

- People

- Economy

- Government and society

- Cultural life

- History

- Presidents of the United States

- Vice presidents of the United States

- First ladies of the United States

- State maps, flags, and seals

- State nicknames and symbols

Fast Facts

Top Questions

- What is the United States?

- Should the United States maintain its embargo against Cuba?

- Should the United States continue its use of drone strikes abroad?

- Should election day in the United States be made a national holiday?

Read Next

- 14 Questions About Government in the United States Answered

- What State Is Washington, D.C. In?

- Timeline of the American Revolution

- 25 Decade-Defining Events in U.S. History

- Have Any U.S. Presidents Decided Not to Run For a Second Term?

Quizzes

- U.S. History Highlights: Part One

- USA Capitals and Nicknames Quiz

- American History and Politics Quiz

- U.S. History Highlights: Part Two

- U.S. State Mottoes

Media

More

HomeGeography & TravelCountries of the World

United States

PrintCiteShareFeedback

Also known as: America, U.S., U.S.A., United States of America

Written by

Adam Gopnik,

Warren W. Hassler,

Richard R. BeemanSee All

Fact-checked by

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica

Last Updated: May 13, 2023 • Article History

flag of the United States of America

Audio File: Anthem of United States (see article)

See all mediaHead Of State And Government: President: Joe BidenCapital: Washington, D.C.Population: 331,449,281; (2023 est.) 339,277,0002Currency Exchange Rate: 1 US dollar equals 0.916 euroForm Of Government: federal republic with two legislative houses (Senate [100]; House of Representatives [4351])…(Show more)

Recent News

May. 13, 2023, 4:34 PM ET (AP)

This tribe’s land was cut in two by US borders. Its fight for access could help dozens of others

For four hours, Raymond V. Buelna, a cultural leader for the Pascua Yaqui Tribe, sat on a metal bench in a concrete holding space at the U.S.-Mexico border, separated from the two people he was taking to an Easter ceremony on tribal land in Arizona and wondering when they might be released

May. 13, 2023, 4:01 PM ET (AP)

End of Title 42 hasn’t stopped migrants’ push north to US from across the Americas

Confusion has rippled from the U.S.-Mexico border to migrant routes across the Americas, as migrants scramble to understand complex and ever-changing laws

Show More

Top Questions

What is the United States?

Should the United States maintain its embargo against Cuba?

Should the United States continue its use of drone strikes abroad?

Should election day in the United States be made a national holiday?

United States, officially United States of America, abbreviated U.S. or U.S.A., byname America, country in North America, a federal republic of 50 states. Besides the 48 conterminous states that occupy the middle latitudes of the continent, the United States includes the state of Alaska, at the northwestern extreme of North America, and the island state of Hawaii, in the mid-Pacific Ocean. The conterminous states are bounded on the north by Canada, on the east by the Atlantic Ocean, on the south by the Gulf of Mexico and Mexico, and on the west by the Pacific Ocean. The United States is the fourth largest country in the world in area (after Russia, Canada, and China). The national capital is Washington, which is coextensive with the District of Columbia, the federal capital region created in 1790.

The major characteristic of the United States is probably its great variety. Its physical environment ranges from the Arctic to the subtropical, from the moist rain forest to the arid desert, from the rugged mountain peak to the flat prairie. Although the total population of the United States is large by world standards, its overall population density is relatively low. The country embraces some of the world’s largest urban concentrations as well as some of the most extensive areas that are almost devoid of habitation.

The United States contains a highly diverse population. Unlike a country such as China that largely incorporated indigenous peoples, the United States has a diversity that to a great degree has come from an immense and sustained global immigration. Probably no other country has a wider range of racial, ethnic, and cultural types than does the United States. In addition to the presence of surviving Native Americans (including American Indians, Aleuts, and Eskimos) and the descendants of Africans taken as enslaved persons to the New World, the national character has been enriched, tested, and constantly redefined by the tens of millions of immigrants who by and large have come to America hoping for greater social, political, and economic opportunities than they had in the places they left. (It should be noted that although the terms “America” and “Americans” are often used as synonyms for the United States and its citizens, respectively, they are also used in a broader sense for North, South, and Central America collectively and their citizens.)

The United States is the world’s greatest economic power, measured in terms of gross domestic product (GDP). The nation’s wealth is partly a reflection of its rich natural resources and its enormous agricultural output, but it owes more to the country’s highly developed industry. Despite its relative economic self-sufficiency in many areas, the United States is the most important single factor in world trade by virtue of the sheer size of its economy. Its exports and imports represent major proportions of the world total. The United States also impinges on the global economy as a source of and as a destination for investment capital. The country continues to sustain an economic life that is more diversified than any other on Earth, providing the majority of its people with one of the world’s highest standards of living.Britannica QuizGeography Fun Facts

The United States is relatively young by world standards, being less than 250 years old; it achieved its current size only in the mid-20th century. America was the first of the European colonies to separate successfully from its motherland, and it was the first nation to be established on the premise that sovereignty rests with its citizens and not with the government. In its first century and a half, the country was mainly preoccupied with its own territorial expansion and economic growth and with social debates that ultimately led to civil war and a healing period that is still not complete. In the 20th century the United States emerged as a world power, and since World War II it has been one of the preeminent powers. It has not accepted this mantle easily nor always carried it willingly; the principles and ideals of its founders have been tested by the pressures and exigencies of its dominant status. The United States still offers its residents opportunities for unparalleled personal advancement and wealth. However, the depletion of its resources, the contamination of its environment, and the continuing social and economic inequality that perpetuates areas of poverty and blight all threaten the fabric of the country.

The District of Columbia is discussed in the article Washington. For discussion of other major U.S. cities, see the articles Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, New Orleans, New York City, Philadelphia, and San Francisco. Political units in association with the United States include Puerto Rico, discussed in the article Puerto Rico, and several Pacific islands, discussed in Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, and American Samoa.

Get a Britannica Premium subscription and gain access to exclusive content.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica

Land

The two great sets of elements that mold the physical environment of the United States are, first, the geologic, which determines the main patterns of landforms, drainage, and mineral resources and influences soils to a lesser degree, and, second, the atmospheric, which dictates not only climate and weather but also in large part the distribution of soils, plants, and animals. Although these elements are not entirely independent of one another, each produces on a map patterns that are so profoundly different that essentially they remain two separate geographies. (Since this article covers only the conterminous United States, see also the articles Alaska and Hawaii.)

Relief

The centre of the conterminous United States is a great sprawling interior lowland, reaching from the ancient shield of central Canada on the north to the Gulf of Mexico on the south. To east and west this lowland rises, first gradually and then abruptly, to mountain ranges that divide it from the sea on both sides. The two mountain systems differ drastically. The Appalachian Mountains on the east are low, almost unbroken, and in the main set well back from the Atlantic. From New York to the Mexican border stretches the low Coastal Plain, which faces the ocean along a swampy, convoluted coast. The gently sloping surface of the plain extends out beneath the sea, where it forms the continental shelf, which, although submerged beneath shallow ocean water, is geologically identical to the Coastal Plain. Southward the plain grows wider, swinging westward in Georgia and Alabama to truncate the Appalachians along their southern extremity and separate the interior lowland from the Gulf.

West of the Central Lowland is the mighty Cordillera, part of a global mountain system that rings the Pacific basin. The Cordillera encompasses fully one-third of the United States, with an internal variety commensurate with its size. At its eastern margin lie the Rocky Mountains, a high, diverse, and discontinuous chain that stretches all the way from New Mexico to the Canadian border. The Cordillera’s western edge is a Pacific coastal chain of rugged mountains and inland valleys, the whole rising spectacularly from the sea without benefit of a coastal plain. Pent between the Rockies and the Pacific chain is a vast intermontane complex of basins, plateaus, and isolated ranges so large and remarkable that they merit recognition as a region separate from the Cordillera itself.

These regions—the Interior Lowlands and their upland fringes, the Appalachian Mountain system, the Atlantic Plain, the Western Cordillera, and the Western Intermontane Region—are so various that they require further division into 24 major subregions, or provinces.

The Interior Lowlands and their upland fringes

Andrew Jackson is supposed to have remarked that the United States begins at the Alleghenies, implying that only west of the mountains, in the isolation and freedom of the great Interior Lowlands, could people finally escape Old World influences. Whether or not the lowlands constitute the country’s cultural core is debatable, but there can be no doubt that they comprise its geologic core and in many ways its geographic core as well.

This enormous region rests upon an ancient, much-eroded platform of complex crystalline rocks that have for the most part lain undisturbed by major orogenic (mountain-building) activity for more than 600,000,000 years. Over much of central Canada, these Precambrian rocks are exposed at the surface and form the continent’s single largest topographical region, the formidable and ice-scoured Canadian Shield.

In the United States most of the crystalline platform is concealed under a deep blanket of sedimentary rocks. In the far north, however, the naked Canadian Shield extends into the United States far enough to form two small but distinctive landform regions: the rugged and occasionally spectacular Adirondack Mountains of northern New York and the more-subdued and austere Superior Upland of northern Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan. As in the rest of the shield, glaciers have stripped soils away, strewn the surface with boulders and other debris, and obliterated preglacial drainage systems. Most attempts at farming in these areas have been abandoned, but the combination of a comparative wilderness in a northern climate, clear lakes, and white-water streams has fostered the development of both regions as year-round outdoor recreation areas.

Mineral wealth in the Superior Upland is legendary. Iron lies near the surface and close to the deepwater ports of the upper Great Lakes. Iron is mined both north and south of Lake Superior, but best known are the colossal deposits of Minnesota’s Mesabi Range, for more than a century one of the world’s richest and a vital element in America’s rise to industrial power. In spite of depletion, the Minnesota and Michigan mines still yield a major proportion of the country’s iron and a significant percentage of the world’s supply.

South of the Adirondack Mountains and the Superior Upland lies the boundary between crystalline and sedimentary rocks; abruptly, everything is different. The core of this sedimentary region—the heartland of the United States—is the great Central Lowland, which stretches for 1,500 miles (2,400 kilometres) from New York to central Texas and north another 1,000 miles to the Canadian province of Saskatchewan. To some, the landscape may seem dull, for heights of more than 2,000 feet (600 metres) are unusual, and truly rough terrain is almost lacking. Landscapes are varied, however, largely as the result of glaciation that directly or indirectly affected most of the subregion. North of the Missouri–Ohio river line, the advance and readvance of continental ice left an intricate mosaic of boulders, sand, gravel, silt, and clay and a complex pattern of lakes and drainage channels, some abandoned, some still in use. The southern part of the Central Lowland is quite different, covered mostly with loess (wind-deposited silt) that further subdued the already low relief surface. Elsewhere, especially near major rivers, postglacial streams carved the loess into rounded hills, and visitors have aptly compared their billowing shapes to the waves of the sea. Above all, the loess produces soil of extraordinary fertility. As the Mesabi iron was a major source of America’s industrial wealth, its agricultural prosperity has been rooted in Midwestern loess.

The Central Lowland resembles a vast saucer, rising gradually to higher lands on all sides. Southward and eastward, the land rises gradually to three major plateaus. Beyond the reach of glaciation to the south, the sedimentary rocks have been raised into two broad upwarps, separated from one another by the great valley of the Mississippi River. The Ozark Plateau lies west of the river and occupies most of southern Missouri and northern Arkansas; on the east the Interior Low Plateaus dominate central Kentucky and Tennessee. Except for two nearly circular patches of rich limestone country—the Nashville Basin of Tennessee and the Kentucky Bluegrass region—most of both plateau regions consists of sandstone uplands, intricately dissected by streams. Local relief runs to several hundreds of feet in most places, and visitors to the region must travel winding roads along narrow stream valleys. The soils there are poor, and mineral resources are scanty.

Eastward from the Central Lowland the Appalachian Plateau—a narrow band of dissected uplands that strongly resembles the Ozark Plateau and Interior Low Plateaus in steep slopes, wretched soils, and endemic poverty—forms a transition between the interior plains and the Appalachian Mountains. Usually, however, the Appalachian Plateau is considered a subregion of the Appalachian Mountains, partly on grounds of location, partly because of geologic structure. Unlike the other plateaus, where rocks are warped upward, the rocks there form an elongated basin, wherein bituminous coal has been preserved from erosion. This Appalachian coal, like the Mesabi iron that it complements in U.S. industry, is extraordinary. Extensive, thick, and close to the surface, it has stoked the furnaces of northeastern steel mills for decades and helps explain the huge concentration of heavy industry along the lower Great Lakes.

The western flanks of the Interior Lowlands are the Great Plains, a territory of awesome bulk that spans the full distance between Canada and Mexico in a swath nearly 500 miles (800 km) wide. The Great Plains were built by successive layers of poorly cemented sand, silt, and gravel—debris laid down by parallel east-flowing streams from the Rocky Mountains. Seen from the east, the surface of the Great Plains rises inexorably from about 2,000 feet (600 metres) near Omaha, Nebraska, to more than 6,000 feet (1,825 metres) at Cheyenne, Wyoming, but the climb is so gradual that popular legend holds the Great Plains to be flat. True flatness is rare, although the High Plains of western Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and eastern Colorado come close. More commonly, the land is broadly rolling, and parts of the northern plains are sharply dissected into badlands.

The main mineral wealth of the Interior Lowlands derives from fossil fuels. Coal occurs in structural basins protected from erosion—high-quality bituminous in the Appalachian, Illinois, and western Kentucky basins; and subbituminous and lignite in the eastern and northwestern Great Plains. Petroleum and natural gas have been found in nearly every state between the Appalachians and the Rockies, but the Midcontinent Fields of western Texas and the Texas Panhandle, Oklahoma, and Kansas surpass all others. Aside from small deposits of lead and zinc, metallic minerals are of little importance.

The Appalachian Mountain system

The Appalachians dominate the eastern United States and separate the Eastern Seaboard from the interior with a belt of subdued uplands that extends nearly 1,500 miles (2,400 km) from northeastern Alabama to the Canadian border. They are old, complex mountains, the eroded stumps of much greater ranges. Present topography results from erosion that has carved weak rocks away, leaving a skeleton of resistant rocks behind as highlands. Geologic differences are thus faithfully reflected in topography. In the Appalachians these differences are sharply demarcated and neatly arranged, so that all the major subdivisions except New England lie in strips parallel to the Atlantic and to one another.

The core of the Appalachians is a belt of complex metamorphic and igneous rocks that stretches all the way from Alabama to New Hampshire. The western side of this belt forms the long slender rampart of the Blue Ridge Mountains, containing the highest elevations in the Appalachians (Mount Mitchell, North Carolina, 6,684 feet [2,037 metres]) and some of its most handsome mountain scenery. On its eastern, or seaward, side the Blue Ridge descends in an abrupt and sometimes spectacular escarpment to the Piedmont, a well-drained, rolling land—never quite hills, but never quite a plain. Before the settlement of the Midwest the Piedmont was the most productive agricultural region in the United States, and several Pennsylvania counties still consistently report some of the highest farm yields per acre in the entire country.

West of the crystalline zone, away from the axis of primary geologic deformation, sedimentary rocks have escaped metamorphism but are compressed into tight folds. Erosion has carved the upturned edges of these folded rocks into the remarkable Ridge and Valley country of the western Appalachians. Long linear ridges characteristically stand about 1,000 feet (300 metres) from base to crest and run for tens of miles, paralleled by broad open valleys of comparable length. In Pennsylvania, ridges run unbroken for great distances, occasionally turning abruptly in a zigzag pattern; by contrast, the southern ridges are broken by faults and form short, parallel segments that are lined up like magnetized iron filings. By far the largest valley—and one of the most important routes in North America—is the Great Valley, an extraordinary trench of shale and limestone that runs nearly the entire length of the Appalachians. It provides a lowland passage from the middle Hudson valley to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, and on southward, where it forms the Shenandoah and Cumberland valleys, and has been one of the main paths through the Appalachians since pioneer times. In New England it is floored with slates and marbles and forms the Valley of Vermont, one of the few fertile areas in an otherwise mountainous region.

Topography much like that of the Ridge and Valley is found in the Ouachita Mountains of western Arkansas and eastern Oklahoma, an area generally thought to be a detached continuation of Appalachian geologic structure, the intervening section buried beneath the sediments of the lower Mississippi valley.

The once-glaciated New England section of the Appalachians is divided from the rest of the chain by an indentation of the Atlantic. Although almost completely underlain by crystalline rocks, New England is laid out in north–south bands, reminiscent of the southern Appalachians. The rolling, rocky hills of southeastern New England are not dissimilar to the Piedmont, while, farther northwest, the rugged and lofty White Mountains are a New England analogue to the Blue Ridge. (Mount Washington, New Hampshire, at 6,288 feet [1,917 metres], is the highest peak in the northeastern United States.) The westernmost ranges—the Taconics, Berkshires, and Green Mountains—show a strong north–south lineation like the Ridge and Valley. Unlike the rest of the Appalachians, however, glaciation has scoured the crystalline rocks much like those of the Canadian Shield, so that New England is best known for its picturesque landscape, not for its fertile soil.

Typical of diverse geologic regions, the Appalachians contain a great variety of minerals. Only a few occur in quantities large enough for sustained exploitation, notably iron in Pennsylvania’s Blue Ridge and Piedmont and the famous granites, marbles, and slates of northern New England. In Pennsylvania the Ridge and Valley region contains one of the world’s largest deposits of anthracite coal, once the basis of a thriving mining economy; many of the mines are now shut, oil and gas having replaced coal as the major fuel used to heat homes.

The Atlantic Plain

The eastern and southeastern fringes of the United States are part of the outermost margins of the continental platform, repeatedly invaded by the sea and veneered with layer after layer of young, poorly consolidated sediments. Part of this platform now lies slightly above sea level and forms a nearly flat and often swampy coastal plain, which stretches from Cape Cod, Massachusetts, to beyond the Mexican border. Most of the platform, however, is still submerged, so that a band of shallow water, the continental shelf, parallels the Atlantic and Gulf coasts, in some places reaching 250 miles (400 km) out to sea.

The Atlantic Plain slopes so gently that even slight crustal upwarping can shift the coastline far out to sea at the expense of the continental shelf. The peninsula of Florida is just such an upwarp: nowhere in its 400-mile (640-km) length does the land rise more than 350 feet (100 metres) above sea level; much of the southern and coastal areas rise less than 10 feet (3 metres) and are poorly drained and dangerously exposed to Atlantic storms. Downwarps can result in extensive flooding. North of New York City, for example, the weight of glacial ice depressed most of the Coastal Plain beneath the sea, and the Atlantic now beats directly against New England’s rock-ribbed coasts. Cape Cod, Long Island (New York), and a few offshore islands are all that remain of New England’s drowned Coastal Plain. Another downwarp lies perpendicular to the Gulf coast and guides the course of the lower Mississippi. The river, however, has filled with alluvium what otherwise would be an arm of the Gulf, forming a great inland salient of the Coastal Plain called the Mississippi Embayment.

South of New York the Coastal Plain gradually widens, but ocean water has invaded the lower valleys of most of the coastal rivers and has turned them into estuaries. The greatest of these is Chesapeake Bay, merely the flooded lower valley of the Susquehanna River and its tributaries, but there are hundreds of others. Offshore a line of sandbars and barrier beaches stretches intermittently the length of the Coastal Plain, hampering entry of shipping into the estuaries but providing the eastern United States with a playground that is more than 1,000 miles (1,600 km) long.

Poor soils are the rule on the Coastal Plain, though rare exceptions have formed some of America’s most famous agricultural regions—for example, the citrus country of central Florida’s limestone uplands and the Cotton Belt of the Old South, once centred on the alluvial plain of the Mississippi and belts of chalky black soils of eastern Texas, Alabama, and Mississippi. The Atlantic Plain’s greatest natural wealth derives from petroleum and natural gas trapped in domal structures that dot the Gulf Coast of eastern Texas and Louisiana. Onshore and offshore drilling have revealed colossal reserves of oil and natural gas.

The Western Cordillera

West of the Great Plains the United States seems to become a craggy land whose skyline is rarely without mountains—totally different from the open plains and rounded hills of the East. On a map the alignment of the two main chains—the Rocky Mountains on the east, the Pacific ranges on the west—tempts one to assume a geologic and hence topographic homogeneity. Nothing could be farther from the truth, for each chain is divided into widely disparate sections.

The Rockies are typically diverse. The Southern Rockies are composed of a disconnected series of lofty elongated upwarps, their cores made of granitic basement rocks, stripped of sediments, and heavily glaciated at high elevations. In New Mexico and along the western flanks of the Colorado ranges, widespread volcanism and deformation of colourful sedimentary rocks have produced rugged and picturesque country, but the characteristic central Colorado or southern Wyoming range is impressively austere rather than spectacular. The Front Range west of Denver is prototypical, rising abruptly from its base at about 6,000 feet (1,825 metres) to rolling alpine meadows between 11,000 and 12,000 feet (3,350 and 3,650 metres). Peaks appear as low hills perched on this high-level surface, so that Colorado, for example, boasts 53 mountains over 14,000 feet (4,270 metres) but not one over 14,500 feet (4,420 metres).

The Middle Rockies cover most of west-central Wyoming. Most of the ranges resemble the granitic upwarps of Colorado, but thrust faulting and volcanism have produced varied and spectacular country to the west, some of which is included in Grand Teton and Yellowstone national parks. Much of the subregion, however, is not mountainous at all but consists of extensive intermontane basins and plains—largely floored with enormous volumes of sedimentary waste eroded from the mountains themselves. Whole ranges have been buried, producing the greatest gap in the Cordilleran system, the Wyoming Basin—resembling in geologic structure and topography an intermontane peninsula of the Great Plains. As a result, the Rockies have never posed an important barrier to east–west transportation in the United States; all major routes, from the Oregon Trail to interstate highways, funnel through the basin, essentially circumventing the main ranges of the Rockies.

The Northern Rockies contain the most varied mountain landscapes of the Cordillera, reflecting a corresponding geologic complexity. The region’s backbone is a mighty series of batholiths—huge masses of molten rock that slowly cooled below the surface and were later uplifted. The batholiths are eroded into rugged granitic ranges, which, in central Idaho, compose the most extensive wilderness country in the conterminous United States. East of the batholiths and opposite the Great Plains, sediments have been folded and thrust-faulted into a series of linear north–south ranges, a southern extension of the spectacular Canadian Rockies. Although elevations run 2,000 to 3,000 feet (600 to 900 metres) lower than the Colorado Rockies (most of the Idaho Rockies lie well below 10,000 feet [3,050 metres]), increased rainfall and northern latitude have encouraged glaciation—there as elsewhere a sculptor of handsome alpine landscape.Britannica QuizGeography Fun Facts

The western branch of the Cordillera directly abuts the Pacific Ocean. This coastal chain, like its Rocky Mountain cousins on the eastern flank of the Cordillera, conceals bewildering complexity behind a facade of apparent simplicity. At first glance the chain consists merely of two lines of mountains with a discontinuous trough between them. Immediately behind the coast is a line of hills and low mountains—the Pacific Coast Ranges. Farther inland, averaging 150 miles (240 km) from the coast, the line of the Sierra Nevada and the Cascade Range includes the highest elevations in the conterminous United States. Between these two unequal mountain lines is a discontinuous trench, the Troughs of the Coastal Margin.

The apparent simplicity disappears under the most cursory examination. The Pacific Coast Ranges actually contain five distinct sections, each of different geologic origin and each with its own distinctive topography. The Transverse Ranges of southern California are a crowded assemblage of islandlike faulted ranges, with peak elevations of more than 10,000 feet but sufficiently separated by plains and low passes so that travel through them is easy. From Point Conception to the Oregon border, however, the main California Coast Ranges are entirely different, resembling the Appalachian Ridge and Valley region, with low linear ranges that result from erosion of faulted and folded rocks. Major faults run parallel to the low ridges, and the greatest—the notorious San Andreas Fault—was responsible for the earthquake that all but destroyed San Francisco in 1906. Along the California–Oregon border, everything changes again. In this region, the wildly rugged Klamath Mountains represent a western salient of interior structure reminiscent of the Idaho Rockies and the northern Sierra Nevada. In western Oregon and southwestern Washington the Coast Ranges are also different—a gentle, hilly land carved by streams from a broad arch of marine deposits interbedded with tabular lavas. In the northernmost part of the Coast Ranges and the remote northwest, a domal upwarp has produced the Olympic Mountains; its serrated peaks tower nearly 8,000 feet (2,440 metres) above Puget Sound and the Pacific, and the heavy precipitation on its upper slopes supports the largest active glaciers in the United States outside of Alaska.

East of these Pacific Coast Ranges the Troughs of the Coastal Margin contain the only extensive lowland plains of the Pacific margin—California’s Central Valley, Oregon’s Willamette River valley, and the half-drowned basin of Puget Sound in Washington. Parts of an inland trench that extends for great distances along the east coast of the Pacific, similar valleys occur in such diverse areas as Chile and the Alaska panhandle. These valleys are blessed with superior soils, easily irrigated, and very accessible from the Pacific. They have enticed settlers for more than a century and have become the main centres of population and economic activity for much of the U.S. West Coast.

Still farther east rise the two highest mountain chains in the conterminous United States—the Cascades and the Sierra Nevada. Aside from elevation, geographic continuity, and spectacular scenery, however, the two ranges differ in almost every important respect. Except for its northern section, where sedimentary and metamorphic rocks occur, the Sierra Nevada is largely made of granite, part of the same batholithic chain that creates the Idaho Rockies. The range is grossly asymmetrical, the result of massive faulting that has gently tilted the western slopes toward the Central Valley but has uplifted the eastern side to confront the interior with an escarpment nearly two miles high. At high elevation glaciers have scoured the granites to a gleaming white, while on the west the ice has carved spectacular valleys such as the Yosemite. The loftiest peak in the Sierras is Mount Whitney, which at 14,494 feet (4,418 metres) is the highest mountain in the conterminous states. The upfaulting that produced Mount Whitney is accompanied by downfaulting that formed nearby Death Valley, at 282 feet (86 metres) below sea level the lowest point in North America.

The Cascades are made largely of volcanic rock; those in northern Washington contain granite like the Sierras, but the rest are formed from relatively recent lava outpourings of dun-coloured basalt and andesite. The Cascades are in effect two ranges. The lower, older range is a long belt of upwarped lava, rising unspectacularly to elevations between 6,000 and 8,000 feet (1,825 and 2,440 metres). Perched above the “low Cascades” is a chain of lofty volcanoes that punctuate the horizon with magnificent glacier-clad peaks. The highest is Mount Rainier, which at 14,410 feet (4,392 metres) is all the more dramatic for rising from near sea level. Most of these volcanoes are quiescent, but they are far from extinct. Mount Lassen in northern California erupted violently in 1914, as did Mount St. Helens in the state of Washington in 1980. Most of the other high Cascade volcanoes exhibit some sign of seismic activity.

The Western Intermontane Region

The Cordillera’s two main chains enclose a vast intermontane region of arid basins, plateaus, and isolated mountain ranges that stretches from the Mexican border nearly to Canada and extends 600 miles from east to west. This enormous territory contains three huge subregions, each with a distinctive geologic history and its own striking topography.

The Colorado Plateau, nestled against the western flanks of the Southern Rockies, is an extraordinary island of geologic stability set in the turbulent sea of Cordilleran tectonic activity. Stability was not absolute, of course, so that parts of the plateau are warped and injected with volcanics, but in general the landscape results from the erosion by streams of nearly flat-lying sedimentary rocks. The result is a mosaic of angular mesas, buttes, and steplike canyons intricately cut from rocks that often are vividly coloured. Large areas of the plateau are so improbably picturesque that they have been set aside as national preserves. The Grand Canyon of the Colorado River is the most famous of several dozen such areas.

West of the plateau and abutting the Sierra Nevada’s eastern escarpment lies the arid Basin and Range subregion, among the most remarkable topographic provinces of the United States. The Basin and Range extends from southern Oregon and Idaho into northern Mexico. Rocks of great complexity have been broken by faulting, and the resulting blocks have tumbled, eroded, and been partly buried by lava and alluvial debris accumulating in the desert basins. The eroded blocks form mountain ranges that are characteristically dozens of miles long, several thousand feet from base to crest, with peak elevations that rarely rise to more than 10,000 feet, and almost always aligned roughly north–south. The basin floors are typically alluvium and sometimes salt marshes or alkali flats.

The third intermontane region, the Columbia Basin, is literally the last, for in some parts its rocks are still being formed. Its entire area is underlain by innumerable tabular lava flows that have flooded the basin between the Cascades and Northern Rockies to undetermined depths. The volume of lava must be measured in thousands of cubic miles, for the flows blanket large parts of Washington, Oregon, and Idaho and in southern Idaho have drowned the flanks of the Northern Rocky Mountains in a basaltic sea. Where the lavas are fresh, as in southern Idaho, the surface is often nearly flat, but more often the floors have been trenched by rivers—conspicuously the Columbia and the Snake—or by glacial floodwaters that have carved an intricate system of braided canyons in the remarkable Channeled Scablands of eastern Washington. In surface form the eroded lava often resembles the topography of the Colorado Plateau, but the gaudy colours of the Colorado are replaced here by the sombre black and rusty brown of weathered basalt.

Most large mountain systems are sources of varied mineral wealth, and the American Cordillera is no exception. Metallic minerals have been taken from most crystalline regions and have furnished the United States with both romance and wealth—the Sierra Nevada gold that provoked the 1849 gold rush, the fabulous silver lodes of western Nevada’s Basin and Range, and gold strikes all along the Rocky Mountain chain. Industrial metals, however, are now far more important; copper and lead are among the base metals, and the more exotic molybdenum, vanadium, and cadmium are mainly useful in alloys.

In the Cordillera, as elsewhere, the greatest wealth stems from fuels. Most major basins contain oil and natural gas, conspicuously the Wyoming Basin, the Central Valley of California, and the Los Angeles Basin. The Colorado Plateau, however, has yielded some of the most interesting discoveries—considerable deposits of uranium and colossal occurrences of oil shale. Oil from the shale, however, probably cannot be economically removed without widespread strip-mining and correspondingly large-scale damage to the environment. Wide exploitation of low-sulfur bituminous coal has been initiated in the Four Corners area of the Colorado Plateau, and open-pit mining has already devastated parts of this once-pristine country as completely as it has West Virginia.

Drainage