1.2.3 The endogenous opioid and the endocannabinoid system

Besides endogenous opioid and cannabinoid receptors, endogenous opioid and

cannabinoid ligands (or endocannabinoids) have also been identified (Fig. 5C and D).

Endogenous opioids are peptide natured neurotransmitters, neuromodulators or even

neurohormones 76,77, and the most notable ones are the enkephalins 58 (Fig. 3), endorphins 78

,

dynorphins 79, nociceptin 80 and endomorphins 81. The endocannabinoids behave as

neuromodulators, and are arachidonic acid derivatives 82,83, such as the arachidonoyl

ethanolamide (anandamide; Fig. 4)

60, 2-arachidonoylglycerol 84 or noladin ether 85

. The

endogenous opioids are synthesized from precursor proteins (prepro-opiomelanocortin,

62 64

61 63 65

9

preproenkephalin and preprodynorphin) 86,87

, while the endocannabinoids are cleaved from

phospholipid membranes or synthesized through the fatty acid synthesis 83. These systems

which comprise the enzymes which synthesize and degrade endogenous opioids and

endocannabinoids, together with the receptors, which recognize them, are called the

endogenous opioid and endocannabinoid system. Both systems are under strict regulation 83,88

,

however main difference is that the endocannabinoids are not synthesized in advance and

stored in vesicles compared to endogenous opioids 89 or other neuromodulators, instead they

are released “on demand” 82,83,90,91

.

Opioid and cannabinoid receptor interactions

It is known that the expression patterns of cannabinoid and opioid receptors overlaps

in several parts of the CNS (see Table I). In certain forebrain regions, such as caudate

putamen, dorsal hippocampus, substantia nigra, and nucleus accumbens, the MOR and CB1

receptors are not only co-localized, but also co-expressed in the same neurons 92–94

. It has also

been shown that these two receptors can be cross-regulated 95 via a direct 96 or indirect

interactions 29,97, and they can also form heterodimers 98. The CB1 and DOR together with

KOR can too allosterically alter each other’s activity 97,99–101 and in case of DOR can form

heteromers as well 101. The interaction between these receptors results many overlapping

physiological functions such as nociception 101–105, mood regulation 106,107, energy and feeding

regulation 108,109, regulation of GI motility 110 or the mediation of ethanol effects 111. There is

also evidence for an interaction between the CB2 and MOR in the mouse forebrain and

brainstem, which was demonstrated by our group 112,113. However the interaction between

opioid and CB2 receptors needs more detailed studies.

Table I The distribution and physiological effects of opioid and cannabinoid receptors

- denotes the CNS regions where opioid and CB1 receptors are proved to interact with each other and

are co-expressed. The table was constructed based on the following publications: 45,74–76,83,102,114–116

11

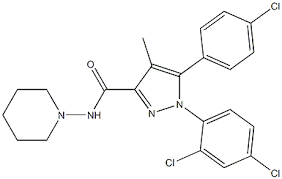

1.3 Rimonabant

1.3.1 The CB1 receptor and appetite, Acomplia®

Increased hunger has been long associated with Cannabis use 117–119

, also there is

extensive evidence that the endocannabinoid system, especially the CB1 receptor is involved

in the control of appetite and feeding (for review see 120).

SR141716, or rimonabant (Fig. 6A) was developed as a highly selective CB1

antagonist, sponsored by Sanofi Aventis (now Sanofi S.A.) 62, with a Ki of 5.6 nM towards its

specific receptor. For comparison, rimonabant binds to CB2 receptors with >1000 nM Ki.

Rimonabant can effectively antagonize most of the effects of different types of CB1 agonist

both in vivo and in vitro 116,121 and according to preclinical animal, and clinical human studies

showed a clear efficacy for the treatment of obesity (for review see: 122,123). In 2006 The

European Commission approved the sale of rimonabant in the European Union and was first

introduced in the United Kingdom under the trade name Acomplia® (Fig. 6B).

The weight-loss effect of rimonabant is believed to be mostly accomplished through

the peripheral CB1 receptors on adipocytes and hepatocytes, by decreasing lipogenesis (for

review see: 120,124). Rimonabant is also able to pass through the blood-brain-barrier (BBB) 121

,

therefore it can interact with CB1 receptors expressed in brain areas which are implicated in

the reinforcing effects of natural reinforces such as food (for review see: 120,124).

1.3.2 The psychiatric side effects and unspecific actions of rimonabant

Interacting with CB1 receptors that are working together with the reinforcing/reward

system might result unspecific actions of rimonabant. Indeed according to Christensen and

colleagues 125 during the clinical trials patient were experiencing psychiatric pathographies

such as anxiety, depression, mood alterations or suicidal thoughts during 20 mg rimonabant

treatment. The psychiatric side effects were also affirmed by the United State Food and Drug

Administration’s (FDA) briefing document (see web reference B

), which led to the

disapproval of rimonabant marketing authorization in the US. These findings were culminated

when four patients committed suicide in the rimonabant group during the study period, which

resulted the withdrawal of rimonabant in 2008 by the European Medicines Agency (see web

reference C

).

12

Many studies revealed that rimonabant can produce effects opposite to cannabinoid

agonist in vivo and in vitro, that is it can behave as an inverse agonist (see section, for review

see 123). It is also believed that its anorectic effect is due this pharmacological property 120,124

.

Additionally, before as well as after entering rimonabant to the market there were several

publications indicating its non-CB1 receptor related actions 126,127, partly its inverse agonistic

effects 126,128–130 and its dose related side effects 125,131,132

. These reports also established a

rather unspecific behavior at higher concentrations (for review see 133,134). Yet again these

unspecific actions can endow rimonabant with promising therapeutical applications in drug

dependence (for review see 135).